Social capital and adult education

Titelvollanzeige

| Autor/in: | Field, John |

|---|---|

| Titel: | Social capital and adult education |

| Jahr: | 2008 |

| Quelle: | deutsche Übersetzung in: Die Österreichische Volkshochschule, Nr. 229, September 2008, S. 2-5. |

Social capital has become a hotly debated topic in recent years. It refers essentially to “social networks, the reciprocities that arise from them, and the value of these for achieving mutual goals” (Schuller, Baron and Field 2000, 1). Since Durkheim, sociologists have examined the nature of social bonds. What is new about the concept of social capital is that it asks us to view a wide range of social connections and networks holistically, in an integrated way; and as a resource, which people deploy in order to advance their interests by co-operating with others.

The concept of social capital rose rapidly across the social sciences largely as a result of one person’s writing. Robert Putnam followed his path-breaking study of the part played by voluntary associations in Italian economic history (Putnam 1993) with a monumental analysis of evidence suggesting a significant decline in civic engagement in the USA (Putnam 2000). Putnam presented data showing that civic engagement in both Italy and the USA appeared to show a strong positive association with education, health, economic prosperity and mental well-being, as well as a clear negative association with crime. The collapse of civic engagement in the USA represented, for Putnam, an absolute disaster. Independently of Putnam, James Coleman had already argued from a functionalist perspective that parental social capital functioned as a social network resource that facilitated children’s educational achievement (Coleman 1988). The concept had also been used by the influential French theorist Pierre Bourdieu, who emphasised the ways in which power and inequality were reinforced through the unequal distribution of social capital across social classes (Bourdieu 1984).

In a short period, this debate has become a very general one, and in my judgement also an important one. It touches a number of social science disciplines, including educational science. It has reached a wider audience of policy makers, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD 2001) and the European Commission (European Commission 2005a). It has even resonated with the wider public, particularly in the USA, where Putnam’s diagnosis echoes many people’s concerns with the excesses of individualism and greed. Exploring the relationship between social capital and adult education is therefore an extremely significant task, with both scientific and practical implications.

Networks as resources for learning

The relationship between social capital and lifelong learning is one area where this approach is starting to be used. Of course, it builds on existing research in related areas. Adult education researchers in a number of countries have explored the relationships between adult education and active citizenship, both historically and in contemporary settings; there are similar bodies of work on adult education and community and adult education and volunteering. So not everything after Putnam is new. Yet if some of the themes in the social capital debate have been around for many years, they have tended to be addressed separately, and with a limited evidence base. The concept of social capital challenges us to undertake empirical enquiry and theoretical analysis of the ways in which people’s networks affect their access to and participation in learning; nor about the ways in which adults’ participation in and orientation towards learning can in turn shape and reshape their social networks.

Do people’s social networks help them to create and exchange skills, knowledge and attitudes that in turn allow them to experience other benefits? If people have more social capital – stronger and more extensive network ties – are they more likely to learn new things than people with less social capital? And is people’s learning affected by the types of network that they have – are networks qualitatively different in nature? Further, does the acquisition of new skills and knowledge affect the ways in which people manage their social relationships? Is adult education part of a modernisation process, even of a radical Entzauberung, which can corrode their commitment to established relationships, and encourage them to take a more individualised view of their interpersonal commitments? Because social networks and learning are both desirable resources – they both help us to enjoy other benefits (including the sheer pleasure of learning something new or extending our friendships) – these questions may also help us to think in new ways about economic development and social cohesion.

The policy dimension

The relationship between social capital and human capital has attracted considerable interest ever since the first publication of James Coleman’s seminal paper (Coleman 1988). Coleman demonstrated that schoolchildren’s performance was influenced positively by the existence of close ties between teachers, parents, neighbours and church ministers. This insight has subsequently been explored in some depth through both a series of replication studies and studies using other approaches (Field 2008). Various studies examine the role of networks in the economy, focussing on two main topics: processes of innovation and knowledge exchange (eg Maskell 2000); and patterns of job search and labour recruitment (Field 2008). Only recently has the focus turned to the role of social capital in processes of skills acquisition and improvement among the adult workforce (e.g. Green et. al. 2003).

The connection between social capital and adult education has recently acquired a wider significance in the European context. It is not only in respect of education and training that the wider European policy agenda has for some years sought to balance the demands of competitiveness with the maintenance of social cohesion; to this has been joined an overarching interest in promoting European citizenship. More recently, the Commission has focussed strongly on economic competitiveness, in the wake of the Lisbon Summit of 2000, but it has continued to emphasise the importance of social renewal as a central element in increased global competitiveness. The Commission’s “social agenda” arising from Lisbon set out the goal of building social capital as one of its basic principles (European Commission 2005a, 2), and it subsequently funded a programme of social capital benchmarking to inform its social policy debate (European Commission 2005b).

The concept of social capital has also been adopted to examine the factors underling economic competitiveness in the regions of the European Union (Mouqué 1999, 63-72). More detailed but exploratory work has also been undertaken by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD 2001), as well as the World Bank (World Bank 2001). These intergovernmental agencies, for all their diversity, see a link between human and social capital as central to the pursuit of a socially sustainable strategy for competitiveness and development.

Social capital as an influence on adult education

Conceptually, the relationship between social capital and adult education is potentially quite complex. People can use their social capital to gain access to skills and knowledge in a variety of ways. For example, they use their connections in a very straightforward way to find out how to do new things such as master a work process, meet regulatory requirements, or tap into a new market. The process can also be more indirect: in a complex and fast-changing training market, reputations are passed from individual to individual, informing people’s choice of provider, and influencing the trust they place in their trainer. At the most general level, the strength of social bonds may shape general attitudes towards innovation and change, as well as determine the capacity of particular groups to survive external shocks or adapt to sudden changes in the external environment. Yet while it is possible that the relationship between social capital and lifelong learning is mutually beneficial, it is equally conceivable that the relationship could be negative. Strong community bonds might reinforce norms of low achievement, for instance, and over reliance on informal mechanisms of information exchange may reduce the demand for more formal and systematic forms of training and education (Field 2005; Strawn 2005).

Generally, the literature on schooling and social capital suggests that strong networks and educational achievement are mutually reinforcing (Schuller, Baron and Field 2000). Researchers into schools attainment and social capital have concluded that shared norms and stable social networks tend to promote both the cognitive and social development of young people, to the extent that social capital may at least partly compensate for other environmental influences such as ethnicity and socio-economic deprivation. Logically, then, it might be concluded that the same must hold largely true for adult learning. If so, then the better the stock of social capital in a region or a community, the greater the capacity for mutual learning and improvements in the quality of human capital.

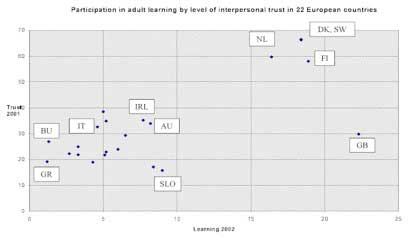

There is some empirical evidence that such a beneficial relationship does in general hold true, at least at the most general level. By combining findings from the World Values Survey with data on adult learning, it is possible at the level of individual countries to show a generally regular and positive association between general levels of (a) interpersonal trust and (b) participation in adult learning (Figure One). At one end, the Scandinavian nations score highly on both levels of trust and on adult participation in learning; at the other, the post-communist nations are ranked low on both scales. Between these two extremes are two other groups: the southern European nations are just below the median on both scales (particularly trust), while the north-central European states such as Austria come just above the median. In all cases, though, there is a clear association between both scores. The only outlier - Britain - is ranked among the middle nations in terms of trust, but has very high levels of adult participation in learning.

At a very broad level, then, it seems that the association between trust and participation in adult learning is reasonably regular and positive. Of course, this judgement must be qualified in a number of ways. Trust can only ever be a very loose proxy indicator of social capital (whose measurement is highly controversial). Survey data on participation in education rely on specific and easily measurable definitions of an activity that is pervasive, distributed and highly subjective. Yet the association is nonetheless so regular as to be striking.

I have also explored this association at individual level through analysis of survey data for Northern Ireland (a fuller analysis is given in Field 2005). At the most general level, the findings suggest a clear association between positive attitudes towards lifelong learning and positive attitudes towards a range of different forms of civic engagement, ranging from church membership to organised sports. So far, then, the survey data appeared to conform to the picture of a mutually beneficial relationship between social capital and lifelong learning. Yet the survey also provides evidence that the association is a complex one.

Essentially, the quantitative survey data fell into what is known as a bimodal pattern: positive attitudes towards lifelong learning were most common among people who thought a given type of civic engagement was important, but also high among people who thought that the same type of civic activity was unimportant. Positive attitudes towards lifelong learning were weakest, by contrast, by those who thought each form of engagement was “neither important nor unimportant”. So the most positive attitudes towards lifelong learning were found among those who have the strongest feelings about civic engagement, with those who are favourable towards engagement regularly showing stronger support for lifelong learning than those who are rather unfavourable, but with both groups clearly outstripping those who do not feel particularly strongly either way. Interestingly, this bimodal pattern was at its strongest in respect of engagement in church-related activities.

Rather than a simple distinction between engagement and disengagement, then, we need to look more closely at the disengaged. In particular, we need to distinguish between the ‘indifferent’ (or passive) and the actively ‘hostile’. In this case, the attitudinal differences between the engaged, the hostile and the indifferent are most marked when it comes to engagement in church-related activity. However, they were least marked when it comes to involvement in community groups. Broadly, then, the responses to this question confirmed the general picture: the highest level of positive attitudes towards an active approach to learning were found among those who are actively engaged, whatever the activity; these are followed by those who are actively hostile; while those who are indifferent show the lowest levels of positive support for an active approach to learning.

There is, then, some evidence to suggest that social capital has clear, if complex, effects on participation in and orientations towards adult education. However, research is at an early stage, and many questions remain as yet unanswered. For example, despite Bourdieu’s hints on the role of social capital in maintaining privilege and hierarchy, little research has so far explored the dimension of socio-economic inequality.

The influence of adult education on social capital

Research into the ways that participation in adult education can influence the ways in which people develop their social networks similarly suggests a positive influence. Of particular importance here is the work of the Research Centre on the Wider Benefits of Learning. Drawing on a range of quantitative and qualitative data, this group of researchers has shown that taking part in adult education classes seems to lead to small but significant increases in participation in voluntary organisations; more strikingly, it also appears to produce an increase in social tolerance (Schuller u.a. 2004).

Some researchers have indicated that social competences can help people make successful transitions. For example, the ability to create new friendship networks appears to be a good predictor of retention among university students (Thomas 2002), while access to informal networks is increasingly decisive in determining outcomes for young people in a risk-prone labour market (Stauber, Pohl and Walther 2007, 9-11). But this remains a relatively under-investigated area, and systematic research into the impact of adult education on people’s informal networks is still lacking.

In admittedly rather speculate manner, Ulrich Beck has claimed that under the highly flexible and uncertain conditions of late modernity, The newly formed social relationships and social networks now have to be individually chosen; social ties, too, are becoming reflexive, so that they have to be established, maintained and constantly renewed by individuals (Beck 1992, 97).

The question of how learning affects network assets in the adult life course is therefore a very important one for further research in the future.

Conclusions

The possible links between social and human capital are highly significant for those scholars and policy makers interested in the social and cultural dimensions of vocational education and training. That there is a relationship between the two is clear from the evidence considered in this piece. Moreover, the relationship is indeed broadly a beneficial one, in that across several indicators, the two appear to be positively associated with one another. We need to avoid an over-simplified distinction between those who are connected and those who are disengaged; the latter category must at least be divided between those who are indifferent and undecided towards a given form of engagement and those who are more definite in their decision not to participate.

Of course, research to date has been relatively limited and the conclusions of this analysis must remain tentative, if not entirely speculative. The evidence considered here is probably best seen as a signpost, pointing out a direction which will be taken further through more substantial research in the future. However, there is sufficient evidence to point generally to a relatively positive influence of social capital on adult education. This has significant implications for policy, given the autonomy of the actors concerned from government, and the resulting risks of unintended consequences. Relatively little is known, so far, about the impact of adult education on social capital, and this must therefore attract further research in the future. What is absolutely clear, though, is that the relationship between these two areas is a highly significant one for policy and practice, as well as for educational science.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste, Routledge, London.

Coleman, J. S. (1988) Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital, American Journal of Sociology, 94, Supplement, 95-120.

European Commission (2005a) Communication from the Commission on the Social Agenda, European Commission, Brussels.

European Commission (2005b) Specifications – Invitation to tender no. VT/2005/025 Establishment of a network on Social Capital, European Commission, Brussels.

Field (2005) Social Capital and Lifelong Learning, Policy Press, Bristol.

Field, J. (2006) Lifelong Learning and the New Educational Order, Trentham Books, Stoke-on-Trent

Field, J. (2008) Social Capital, Routledge, London.

Field, J., Schuller, T. and Baron, S. (2000) Social Capital and Human Capital Revisited, pp. 243-63 in Baron, S., Field, J., and Schuller, T. (eds.) Social Capital: critical perspectives, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Green, A., Preston, J. and Sabates, R. (2003) Education, Equality and Social Cohesion: a distributional approach, Wider Benefits of Learning Research Centre, London.

Maskell, P. (2000) Social Capital, Innovation and Competitiveness, pp. 111-23 in S. Baron, J. Field and T. Schuller (eds.), Social Capital: critical perspectives, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2001) The Well-being of Nations: the role of human and social capital, OECD, Paris.

Putnam, R. D. (1993) Making Democracy Work: Civic traditions in modern Italy, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ.

Putnam, R. D. (2000) Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community, Simon and Schuster, New York.

Schuller, T., Baron, S. and Field, J. (2000), Social Capital: a review and critique, pp. 1-38 in Baron, S., Field, J., and Schuller, T. (eds.) Social Capital: critical perspectives, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Schuller, T., Preston, J., Hammond, C., Bassett-Grundy, A. and Bynner, J. (2004) The Benefits of Learning: The impacts of formal and informal education on social capital, health and family life, Routledge, London.

Stauber, B., Pohl, A. and Walther, A. (2007) Ein neuer Blick auf die Übergänge junger Frauen und Männer, pp. 7-18 in B. Stauber, A. Pohl and A. Walther (eds.), Subjektorientierte Übergangsforschung. Rekonstruktion und Unterstützung biografischer Übergänge junger Erwachsener, Juventa, Weinheim and Munich.

Strawn, C. (2005) Social Capital Influences on Lifelong Learning, paper presented at the International Conference of the Centre for Research in Lifelong Learning, //crll.gcal.ac.uk/conf05/conf_themes.php

Thomas, L. (2002) Student Retention in Higher Education: The role of institutional habitus, Journal of Education Policy, 17, 4, 423-42.

World Bank (2001) World Development Report 2000/2001 - Attacking Poverty, World Bank/Oxford University Press, Washington/New York.